History

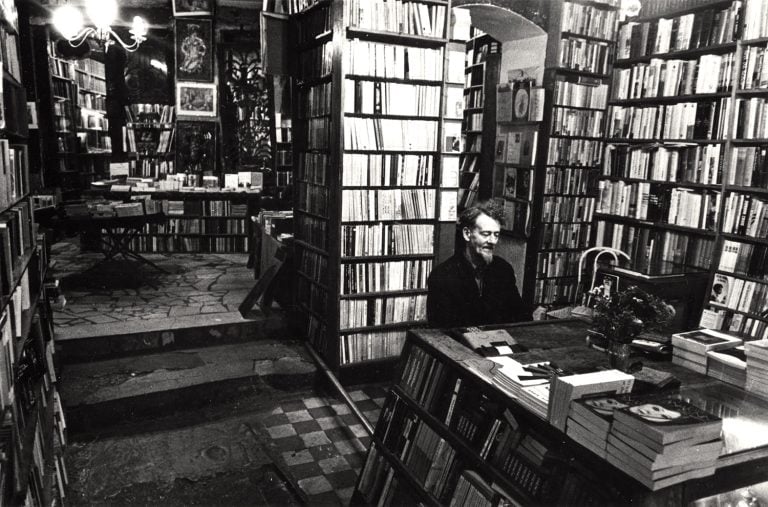

"I created this bookstore like a man would write a novel, building each room like a chapter, and I like people to open the door the way they open a book, a book that leads into a magic world in their imaginations."

A Brief History of a Parisian Bookstore

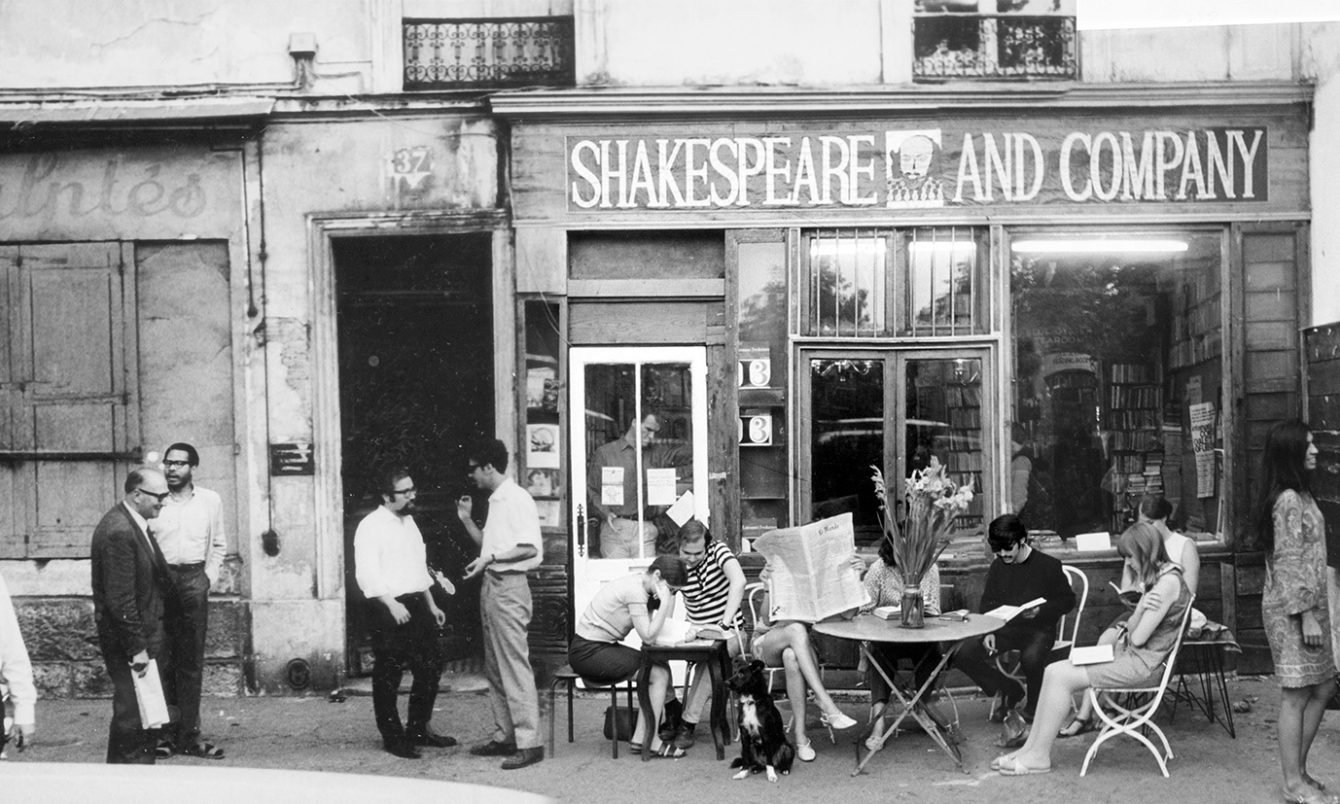

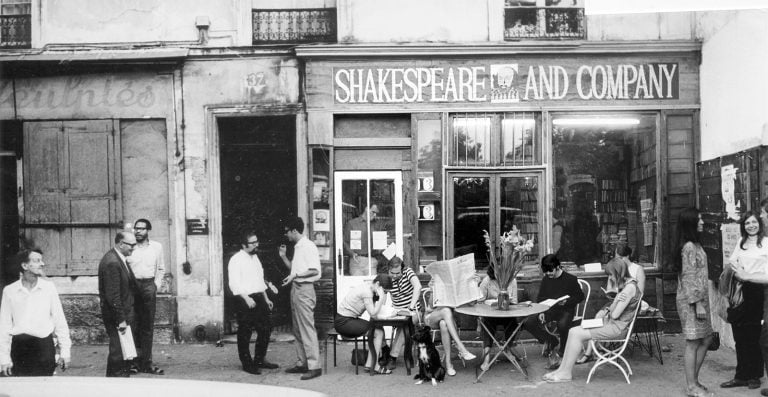

Shakespeare and Company is an English-language bookshop in the heart of Paris, on the banks of the Seine, opposite Notre-Dame. Since opening in 1951, it’s been a meeting place for anglophone writers and readers, becoming a Left Bank literary institution.

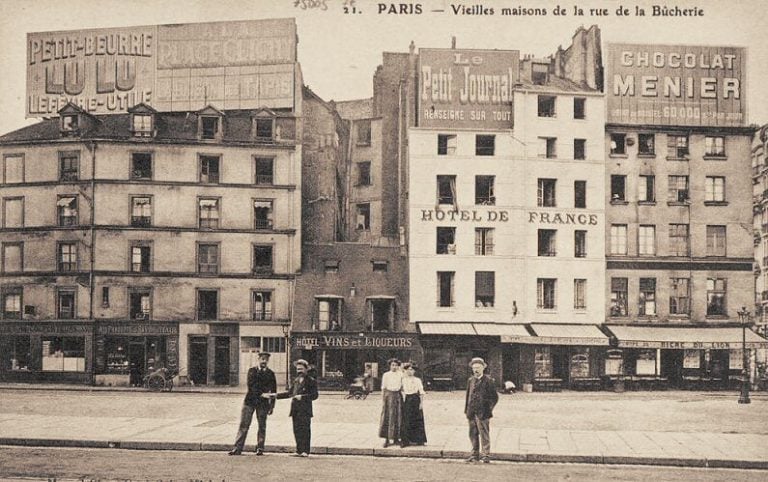

The bookshop was founded by American George Whitman at 37 rue de la Bûcherie, Kilometer Zero, the point at which all French roads begin. Constructed in the early 17th century, the building was originally a monastery, La Maison du Mustier. George liked to pretend he was the sole surviving monk, saying, “In the Middle Ages, each monastery had a frère lampier, a monk whose duty was to light the lamps at nightfall. I’m the frère lampier here now. It’s the modest role I play.”

When the store first opened, it was called Le Mistral. George changed it to the present name in April 1964—on the four-hundredth anniversary of William Shakespeare’s birth—in honor of a bookseller he admired, Sylvia Beach, who’d founded the original Shakespeare and Company in 1919. Her store at 12 rue de l’Odéon was a gathering place for the great expat writers of the time—Joyce, Hemingway, Stein, Fitzgerald, Eliot, Pound—as well as for leading French writers.

Through his bookstore, George Whitman endeavored to carry on the spirit of Beach’s shop, and it quickly became a center for expat literary life in Paris. Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Anaïs Nin, Richard Wright, William Styron, Julio Cortázar, Henry Miller, William Saroyan, Lawrence Durrell, James Jones, and James Baldwin were among early visitors to the shop.

When George was in his early twenties, during the Great Depression, he set out on a “hobo adventure,” as he called it, with only $40 in his pocket. He walked, hitchhiked, and rode the rails from one end of the U.S. to the other, through Mexico, and on to Central America. Acts of generosity experienced on these travels—like the time he fell seriously ill in an isolated part of the Yucatan and was found and nursed back to health by a tribe of Mayans—had a profound effect on him. It inspired his philosophy: “Be not inhospitable to strangers lest they be angels in disguise.”

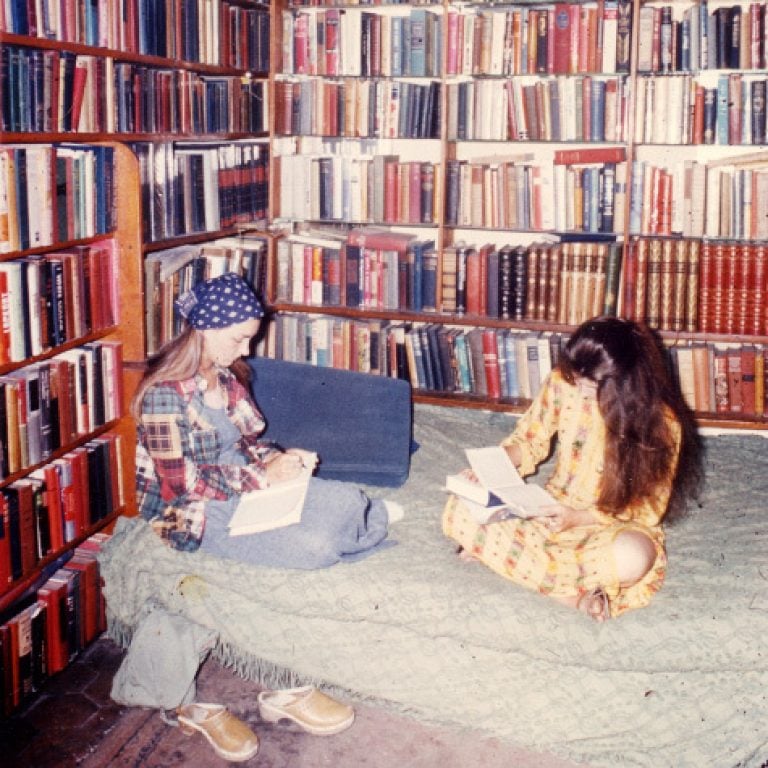

From the first day the store opened, writers, artists, and intellectuals were invited to sleep among the shop’s shelves and piles of books, on small beds that doubled as benches during the day. Since then, an estimated 30,000 young and young-at-heart writers and artists have stayed in the bookshop, including then unknowns such as Alan Sillitoe, Robert Stone, Kate Grenville, Sebastian Barry, Ethan Hawke, Jeet Thayil, Darren Aronofsky, Geoffrey Rush, and David Rakoff. These guests are called Tumbleweeds after the rolling thistles that “drift in and out with the winds of chance,” as George described. A sense of community and commune was very important to him—he referred to his shop as a “socialist utopia masquerading as a bookstore.”

Three things are asked of each Tumbleweed: read a book a day, help at the shop for a few hours a day, and produce a one-page autobiography. Thousands and thousands of these autobiographies have been collected and now form an impressive archive, capturing generations of writers, travelers, and dreamers who have left behind pieces of their stories.

In 2002, at the age of twenty-one, Sylvia Whitman, George’s only child, returned to Shakespeare and Company to spend time with her father, then eighty-eight years old, in his kingdom of books. In 2006, George officially put Sylvia in charge. On the shutters outside the store, he wrote: “Each monastery had a frère lampier whose duty was to light the lamps at nightfall. I have been doing this for fifty years. Now it is my daughter’s turn.”

Sylvia introduced several new literary endeavors. In June 2003, Shakespeare and Company hosted its first literary festival, followed by three others. Participants over the years have included Paul Auster, Will Self, Marjane Satrapi, Jung Chang, Philip Pullman, Hanif Kureishi, Siri Hustvedt, Martin Amis, and Alistair Horne, among many others.

In 2011, with the de Groot Foundation, Shakespeare and Company launched the Paris Literary Prize, a novella contest open to unpublished writers from around the world. In recent years, the bookstore’s had cameo appearances in Richard Linklater’s Before Sunset and Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. Shakespeare and Company also continues to host at least one free literary event a week, and has been delighted to welcome young and emerging writers along with today’s leading authors, such as Zadie Smith, Lydia Davis, John Berger, Jennifer Egan, Carol Ann Duffy, David Simon, Edward St. Aubyn, and Jeanette Winterson.

The shop’s latest projects include a Shakespeare and Company publishing arm.

Although George Whitman passed away on December 14, 2011—two days after his 98th birthday—his novel, this bookshop, is still being written, both by Sylvia and by all the people who continue to read, write, and sleep at Shakespeare and Company.

Thank you all for your support.

About George Whitman

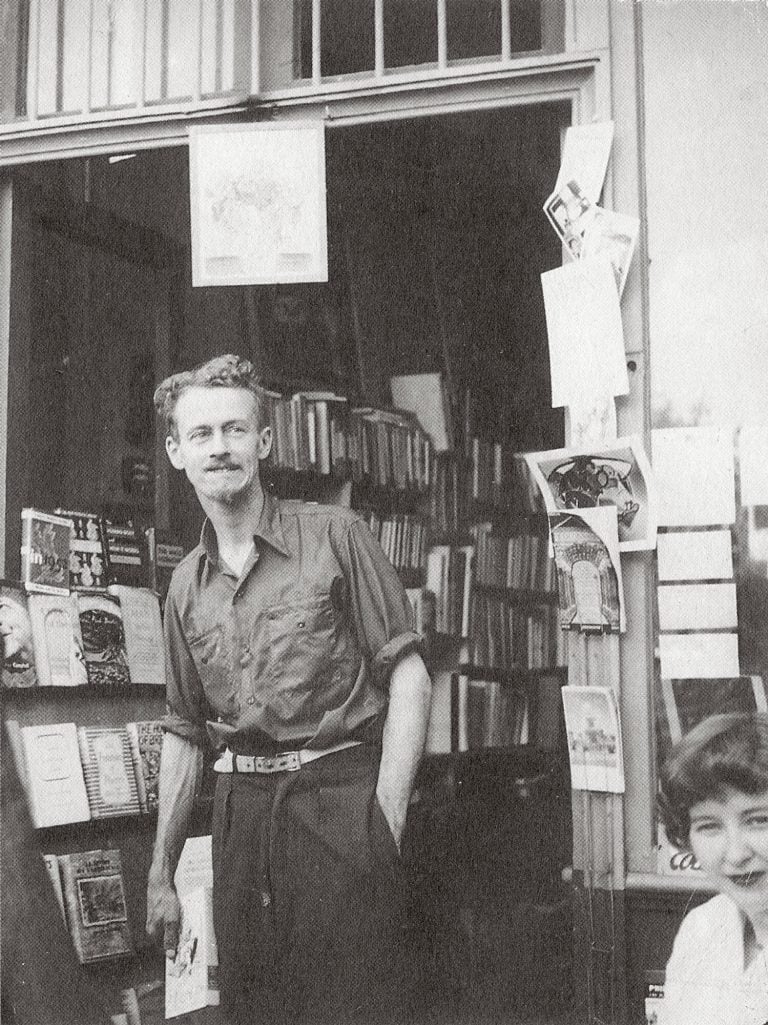

George Whitman, an American, founded Shakespeare and Company at 37 rue de la Bûcherie, Paris, in 1951.

Nicknamed the “Don Quixote of the Latin Quarter,” he was known for his free spirit, his eccentricity, and his generosity—all qualities captured in the verse he inked above the doorway to the bookshop's library: “Be not inhospitable to strangers lest they be angels in disguise.”

Born December 12, 1913, George grew up in Salem, Massachusetts. In 1923, his father, Walter, accepted a teaching post in Nanjing, China, bringing along his wife and children. George loved and revered his years abroad, and this early experience founded his lifelong passion for travel, adventure, and far-flung friends.

In the spring of 1935, in the midst of the Great Depression, George graduated from Boston University with a degree in journalism. It was a difficult time for finding work, so his mother, Grace, was especially pleased when he was offered an assistant reporter’s job in Washington, D.C. George, however, had other ambitions. In July 1935, when he was twenty-one, George set out on a “hobo adventure,” as he called it, hitchhiking, walking, and train-hopping across Mexico, Central America, and the States. He had many adventures and close calls. In an isolated part of the Yucatan, for example, he fell sick with dysentery and was forced to walk alone for three days through the swampy jungle with no food or water. Eventually he was found and nursed back to health by a tribe of Mayans. George was deeply impressed by the fact that, despite hardship and extreme poverty, the people he encountered were invariably friendly and generous. “Give what you can, take what you need” became one of his primary principles.

In 1941, George both registered for the U.S. Army and enrolled at Harvard. At school, he pursued Latin American studies until summer 1942, when he was called into military service. George trained as a medical warrant officer and was stationed at an isolated post in Greenland, used to predict approaching weather on the front.

After George was discharged in 1946, he moved to Paris. Under the G.I. Bill, he enrolled at the Sorbonne, studying psychology and French civilization. He soon took up residence at the Hôtel de Suez on Boulevard Saint-Michel, where he began a lending library of sorts. He had a thousand titles, his door was always left unlocked, and anyone could come in to read or borrow a book.

In 1951, encouraged by his friend Lawrence Ferlinghetti, George founded his bookstore-cum-lending library in a former Algerian grocery, directly across the Seine from Notre-Dame. Originally called Le Mistral, George’s bookshop quickly became a meeting point for the great Paris-based writers of the time: James Baldwin, Anaïs Nin, Julio Cortázar, Lawrence Durrell, Henry Miller, Richard Wright, Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, and William Saroyan, among others.

The bookshop also became a literal home away from home for authors, intellectuals, and artists, who could stay overnight in the shop for free. Over the years, more than 30,000 young and young-at-heart writers have stayed in the bookshop, including then young-unknowns such as Alan Sillitoe, Robert Stone, Kate Grenville, Sebastian Barry, Ethan Hawke, Jeet Thayil, Darren Aronofsky, Geoffrey Rush, and David Rakoff.

Inspired by the legendary bookseller Sylvia Beach (who visited George's bookshop in the 1950s), George adopted the name of her bookstore in April 1964, on the four-hundredth anniversary of the Bard's birth.

In 1981, George's only daughter was born at the Hôtel-Dieu, directly across the Seine from the bookshop. She was given the name Sylvia in honor of Sylvia Beach.

For sixty years, George worked tirelessly to create a home for many thousands of writers and visitors from around the world and to ensure that Shakespeare and Company would be not only a venerable independent bookshop, but also a renowned Left Bank cultural institution. For his lifelong contribution to the arts, George was awarded the Officier des Arts et des Lettres in 2006 by France’s Ministry of Culture.

On December 14, 2011—two days after his 98th birthday—George Whitman died at home, in the apartment above his bookshop. He was buried at Père Lachaise cemetery, surrounded by many of the writers, artists, and intellectuals who inspired his life and his bookshop. George is sorely missed by all his loved ones and by bibliophiles around the world who have read, written, and slept at Shakespeare and Company.

More On George Whitman:

- George’s Obituary in The New York Times

Sylvia Beach's Shakespeare and Company, 1919-1941

Sylvia Beach, an American, founded the first Shakespeare and Company in 1919.

Located in Paris at 12 rue de l’Odéon, the shop was half bookstore and half lending library. It attracted the great expat writers of the time—Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Eliot, Pound—including some of the century’s most compelling female voices: Djuna Barnes, Gertrude Stein, Janet Flanner, Kay Boyle, and Mina Loy.

The bookstore was also frequented by celebrated French authors, such as André Gide, Paul Valéry, and Jules Romains. Beach’s shop served as the writers’ home away from home, postal address, and—when they were desperate—a loan service. Beach also helped usher in modern literature: she published her friend James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922 when no one else dared.

In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway wrote of Beach: “Sylvia had a lively, sharply sculptured face, brown eyes that were as alive as a small animal's and as gay as a young girl's . . . She was kind, cheerful and interested, and loved to make jokes and gossip. No one that I ever knew was nicer to me.” And French author André Chamson said that Beach “did more to link England, the United States, Ireland, and France than four great ambassadors combined.”

Beach’s bookstore was open until 1941, when the Germans occupied Paris. One day that December, a Nazi officer entered her store and demanded Beach’s last copy of Finnegans Wake. Beach declined to sell him the book. The officer said he would return in the afternoon to confiscate all of Beach’s goods and to close her bookstore. After he left, Beach immediately moved all the shop’s books and belongings to an upstairs apartment. In the end, she would spend six months in an internment camp in Vittel, and her bookshop would never reopen.

In 1959, Beach published her memoir, Shakespeare and Company, which begins with her childhood in America and ends with the liberation of Paris after the Second World War. Beach passed away in 1962 in Paris.

Photos of Sylvia Beach courtesy of Princeton University Library

About Tumbleweeds

Throughout his life, George Whitman traveled the world as a self-proclaimed “tumbleweed,” blowing from place to place, sheltered by the grace of strangers.

Wishing to repay the generosity he encountered during his journeys, George founded the bookstore in 1951 with the motto “be not inhospitable to strangers lest they be angels in disguise” and threw open the doors to all sorts of writers, artists, and intellectuals who sought refuge.

In exchange, Tumbleweeds (as guests came to be called) were asked only to “read a book a day,” help out in the shop for a couple of hours, and write a single-page autobiography for George's archives. Today, the bookshop has housed an estimated 30,000 Tumbleweeds, our shelves are crammed with autobiographies and stories of romances played out beneath the beams, and—most importantly—we have no intention of closing our doors.

If you'd like to know more about becoming a Tumbleweed, please go on our dedicated page Tumbleweeding.